Just before Easter this year, I heard an interview on Fresh Air with historian Bart Ehrman on his latest book, How Jesus Became God. It was a fascinating interview, which piqued my interest in early Christian history.

As an evangelical, I always felt a bit hazy on early church history. I tried to learn more about it, about what the earliest Christians were like and believed, but finding useful information seemed difficult. I couldn't find very much beyond legend in Christian media, and secular historians seemed hell-bent on destroying any evidence of legitimacy. Aside from the Acts in the Bible, I didn't really know much at all about early Christianity or how the Bible was put together.

I remember sharing this concern with a pastor friend of mine. I wanted to know how the Bible as we know it today became the canon, and why it happened so late after Jesus' life. I knew it was roughly the fourth century, but I was hazy on who and how. To be honest, it really bothered me that a bunch of Roman Catholics (pre-Martin Luther, which meant to my Protestant mind, a very dubious group of church leaders indeed) seemingly sat down and picked and chose which books "fit" and which ones didn't. I could believe that the Holy Spirit directed them to decide which to choose, but I also could conceive of men "misinterpreting" the Holy Spirit and making mistakes. My pastor friend gave me a book he assured me would help me understand how the books of the Bible were chosen.

I read a chapter of the book and put it down. It made no sense to me, was overly academic and really wasn't assuaging my doubts. From then on, I just sort of allowed myself to forget about it. I allowed it to be one of the few intellectual things I'd simply not pursue and let faith in past knowledge and expertise reign. I wasn't one to do that generally; I like to understand how things work and how things came to be and form my own opinions. But this subject was just too deep - and too treacherous - for me to delve any further into.

The NPR interview with Ehrman, a professor of religious studies at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, re-sparked my interest. His newest book, the one he was being interview about, explained how the earliest followers of Jesus likely viewed him as the Messiah in an earthly sense - the literal human king of the Jews prophesied in Scripture - but upon believing he had risen from the dead, began to believe he was greater than that. This isn't in and of itself entirely foreign to a Christian believer, but what was fascinating is how the early Christians developed their theology of Jesus. From believing he had been adopted as Son by God upon his death and resurrection (or at his baptism) to believing he'd been God incarnate in Mary's womb, to believing he was God before time, the belief in who Jesus was grew and morphed and became increasingly more sophisticated as time - and the educational levels of believers - went on. He uses the New Testament as his primary evidence of these theological changes, using the Gospels and Paul's letters to show the chronological changes in these beliefs through the NT books themselves. I'd read the Gospels countless times, but never realized until he pointed them out, how different each Gospel is - and particularly how different the Gospel of John is, the latest Gospel authored.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. After listening to the interview, I went to order the book. However, it was not yet released at that time, so I ordered one of his older books first, Misquoting Jesus. This book turned out to be the perfect starting point for my studies. It explained how the manuscript we call the Bible today came to be - the very question I'd been wanting answered for years. While it didn't go as late as the Council of Nicaea who eventually formed the canon, it did explain where all the earliest manuscripts came from, and how those manuscripts got copied and distributed. What struck me the most was the fact - one I'd never even heard before - that we don't actually have any of the original manuscripts. Not one. All we have are copies, which were likely copies of copies, if not copies of copies of copies. And of all the copies of each book or letter of the New Testament that are available to scholars today, most of them don't even match each other. Some bear only slight mistakes - spelling, a changed word - but some actually have entirely different sections added or subtracted. Since there is no way of knowing which copies were copied from the originals and which were copied from changed copies, we have no way of knowing what the originals even said.

Furthermore, the originals were not even penned until, at the earliest, twenty years after Jesus' death. The earliest letters of Paul were written twenty years later, and the Gospels were written even later than that, the earliest Gospel Mark being written approximately forty years later and John near the end of the first century, about sixty years later. And they were not penned by the authors the books are named for, but extremely literate foreigners, in Greek no less. The disciples and early followers were uneducated, illiterate Aramaic speakers. These were things I'd never known or considered before.

Misquoting Jesus was a good precursor to How Jesus Became God. It laid the foundation of textual criticism which gets touched on in HJBG. Both books were incredibly enlightening. I know I'd never have been able to read them as a Christian; they'd have come across as more secular Christian history bashing. Except for one thing. One thing that would have bothered me deeply.

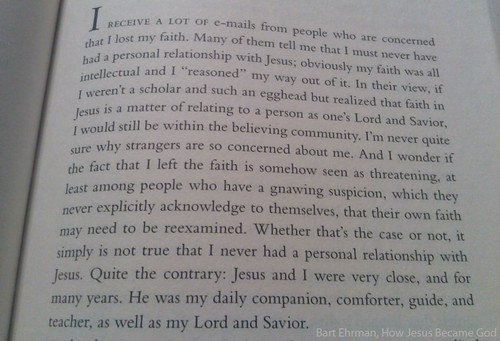

Bart Ehrman was once an evangelical himself. He attended Moody Bible Institute and all.

It was through his study of early church manuscripts and texts that he developed a more "liberal" view of the Bible, seeing it as a very "human" book instead of the inspired word of God. It wasn't this by itself that eventually led to his agnosticism (this is covered in another book, God's Problem, which I've also ordered, though haven't read yet), but it played a large part. Knowing this about his personal history gave these books more credibility to me. He is not a "militant atheist" out to destroy any chance that the Bible might be true. He's a man who once believed in Biblical inerrancy and divine inspiration and who himself once had a "personal relationship with Jesus". He didn't go into the field of textual criticism to debunk Christianity; he went into it to strengthen it.

Bart Ehrman has written several books, and I'd like to get my hands on all of them eventually. So far, I've read the above mentioned two, as well as Did Jesus Exist? (he ardently and scholastically argues yes, he did, even if the other claims about his life are less easy to prove), and have God's Problem and Lost Scriptures: Books That Did Not Make It Into the New Testament waiting on my shelves. The haze of early church beliefs has finally started to lift for me, as I see Christianity for what it really is - an intriguing history of religion and culture, a religion that expanded in nuance and theology through time and gained popularity through Roman politics and power. While I now don't believe in Christianity's claims to be truth anymore, I'm am still interested in it from an historical viewpoint and have become fascinated by its origins.

Hi Lori. This was interesting to read because I've asked these same questions before. I'm surprised to read that you tried to get answers to your questions about how the Bible was formed for many years and couldn't...I, too, have been interested in this topic but found the information with little effort. I am curious about one thing--what has given you confidence that what Ehrman writes is valid? I ask sincerely because in my own research, I have found that you can find "scholars" who say anything across the spectrum about Christianity and Jesus (some believe he was a homosexual magician).

ReplyDeleteInterestingly, it's not just Christians who uphold the Bible as reliable. There are plenty of reputable scholars who say that the manuscript support for the Bible is far and above that of other documents we trust. They believe in the historicity of the documents even if they don't believe Christianity is the only way to God.

It's not possible to address every single thing you mentioned, but one thing I have learned that I want to share is that the Gospels and epistles being written 20-70 years after Christ's crucifixion is not problematic. That is actually a close time period compared with other historical documents that are regarded as reliable, so it's definitely not strange or suspect. Also, that time period is not removed enough for the eyewitnesses and people mentioned in the writings to have already died. Anyone reading the Gospels could have gone to verify the info with those who were mentioned. This is why Luke goes out of his way to say that he interviewed people and checked on the facts himself.

About the manuscripts being copies: There are so many copies of the manuscripts (far far more than comparable historical documents considered valid) that coincide with each other to 95+% accuracy that it doesn't matter what the originals said, believe it or not--because the copies are all saying the same thing and not contradicting each other. You can read about what the differences in the manuscripts are; they are slips of the pen and negligible. Nothing that changes content. This argument is nothing new and has been made for centuries.

Also, any time arguments like this come up, it is only fair to mention the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The scrolls were manuscripts of scriptures older than the manuscripts that had been discovered up to that point, and, again, said the same things as the latest manuscripts we had.

Aside from all this, there are actually lots of scholars who think Ehrman's work is flawed and biased. You can check out their criticisms of his work here:

http://www.godandscience.org/apologetics/new_testament_corruption.html

https://www.youtube.com/user/ehrmanproject

I think it's great that you are hungry to get answers. We should all be willing to consider the evidence. I would be curious to hear your take on what other scholars have to say about Ehrman.

Hi there. There's a lot here to respond to, but basically I'll say this. Ehrman DOES agree with the reliability of the New Testament for general historicity, particularly on early Christians and Jesus' life. While he doesn't necessarily believe the stories themselves (miracles, etc) actually happened (but formed from oral tradition over time), he does agree - as do nearly ALL scholars on the subject - that the documents are reliable for historical purposes. This is actually what annoys atheists who want to claim the New Testament is totally fabricated. He argues that no one who is genuinely scholarly thinks this. So maybe I didn't explain that well enough. In "Did Jesus Exist?" he goes into great detail to debunk the "scholars" who claim that it was all forged, made up, that Jesus never lived, etc. He definitely argues that Jesus was a real man who died by crucifixion under Pilate.

ReplyDeleteHowever, saying all of that, the fact that these stories (the Gospels at least, Paul's early letters are a somewhat different story), were written decades later in another land in another country by another class of people IS significant. Stories that travel that distance over that length of time (even if the time is relatively short when looked at in another way) are bound to grow arms and legs. The fact that the gospels all tell different stories, and the ones that are the same often have very different details, questions the inerrancy of Scripture, which evangelicals hold to dearly. To say Scripture is inerrant just makes no sense - too many stories say too many different things, so even if it was just a slip of the pen, those stories were changed enough to not be inerrant. Also, the "slip of the pen" is true for a lot of discrepancies but not all. Many copies of manuscripts have entirely different passages that are not found in all copies, which appear to be clear additions by later scribes, some trying to interpret a word they don't quite understand and some trying to clarify a theological point. In other words, scribes added things and subtracted things, along with the slip of pens.

Obviously I can't guarantee that Ehrman is not just a fraud, but he is well respected in the arena of textual criticism, and he provides ample detail and proofs in his books to back his claims up.

As for the Dead Sea Scrolls, they are mostly copies of manuscripts from the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) so not really pertinent to the question of Jesus and Christianity per se.

Thanks so much for your interesting comments! I hope I don't sound like I'm arguing with you. I'm trying to respond while cooking dinner, so I'm surely missing some points that deserve comment and possibly rambling a bit.

Thanks!

But that's just it--Ehrman is NOT well-respected by those who know what they're talking about. Did you visit either of the links I gave? I am interested to hear your feedback once you do.

ReplyDelete2. Ehrman's claim that we can't know what the original manuscripts said:

ReplyDeleteAttempting to demonstrate that textual critics face an insurmountable hurdle when attempting to reconstruct the original text, Ehrman cites Celsus again who, “argued that Christians changed the text at will, as if drunk from a drinking bout.”24 He also points out that discrepancies in the Bible were acknowledged in the early Church. “Pope Damascus was so concerned about varieties of Latin manuscripts that he commissioned Jerome to produce a standardized translation.”25

What seems to evade Ehrman is that there appears to have been a standard against which to compare these variants. Otherwise, how could one know that there were variants or the text was changed? Ehrman dubiously cites a chief critic of Christianity as if what Celsus says is uncritically true. Ehrman criticizes the manuscripts that were available to Jerome as, “manuscripts that cannot be trusted.”26

While criticizing the process of transmission, Ehrman ignores the massive variety of New Testament manuscripts and commentaries on the New Testament available to textual critics. Craig Blomberg points out there are more than 5000 manuscripts available in Greek to help identify textual variants and move close to the original text. Unlike Ehrman who give the impression that all textual scholars seem to think that the original text is unrecoverable due to the questionable transmission process, “Scholars of almost every theological stripe attest to the profound care with which the NT books were copied in the Greek language, and later transmitted and preserved in Syriac, Coptic, Latin and a variety of other ancient European and Middle Eastern languages.”27

Moreover, critics have other sources of ancient information to reconstruct much of what is contained in the New Testament. As Professor Kenneth Samples points out, “Even without these thousands of manuscripts, virtually the entire New Testament text could be reproduced from specific scriptural citations within written (and preserved) sermons, commentaries, and various other works of the early church fathers.”28 Ehrman’s apologetic intentions become clear as he seeks to mislead the reader into believing that the New Testament was compiled by a group of illiterate, lazy scribes who cannot be trusted.

Differences in the manuscripts do not necessarily mean contradictions.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v3VBNFhC52A

The authors of the gospels:

ReplyDeletehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4g5cnpO3p8Y